Why are we okay with athletes dying?

Every year, over three thousand young individuals die from sudden cardiac arrest in the United States—with the majority of them being athletes.1 In fact, sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), is both the #1 cause of death among student athletes and #1 cause of death on school campuses.2 Unlike many of the other factors contributing to the loss of life in this population, SCA is largely preventable. So why isn't there more being done to protect our youth? How many more lives have to be cut short before large-scale changes to how we view athletic health occurs?

Sudden Cardiac Arrest and The Healthy Athlete Paradox:

Why athletes, despite being viewed as a population absent of cardiovascular complications, are at heightened risk.

To understand how sudden cardiac arrest affects athletes, we must first define what it is. Sudden cardiac arrest (SCA), as the name suggests, occurs when an underlying cardiovascular abnormality causes the heart to abruptly stop pumping blood. This is often conflated with a heart attack, which occurs when blood flow to the heart is blocked. The distinction is important to make because heart attacks are largely associated with lifestyle choices: think smoking, physical inactivity, high blood pressure, and poor diet. SCA, while it can be affected by such risk factors, can also occur independently of them due to underlying genetic issues.

This independence is what makes SCA particularly dangerous and misunderstood. Unlike a heart attack, it can strike anyone, including those who by all other measures appear healthy. An individual can eat well, have low cholesterol, exercise regularly, and still suffer SCA if they have an undiagnosed heart condition.

"Undiagnosed heart condition" is a bit of a catch-all phrase, so let me clarify what it means in relation to SCA. At a macro level, it's relatively common for someone to have an underlying structural or electrical abnormality that could put them at risk. In fact, it's estimated that around 1 in 300 Americans have an abnormality they don't know about.3 Most people can live long, healthy lives despite this. They can go their entire lives with an abnormality without it interfering in their day-to-day activities or triggering SCA.

But there's an exception to this relative safety and it has everything to do with what the heart is being asked to do. Athletes experience sudden cardiac death (SCD) at a higher rate than non-athletes and face nearly three times the risk of SCA.4 It's not because athletes have more underlying genetic conditions than the rest of the population. Rather, intensive training and physical activity are more likely to trigger an SCA episode in someone with an underlying abnormality.

Think of it this way: if two people had the same cardiac electrical abnormality and one constantly pushed their heart to the limit through strenuous exercise, it makes sense that person would be at higher risk of that abnormality becoming fatal. This is because intense exercise can cause arrhythmias in athletes who have underlying conditions. Beyond genetic predispositions to structural and electrical abnormalities, athletes also face unique risks from acquired abnormalities or conditions developed through their sport itself. These include blunt trauma to the chest, known as commotio cordis; heart inflammation from excessive exercise, or myocarditis; and toxicity from performance-enhancing drugs.

The bottom line is SCA can affect anyone, but a specific set of risk factors makes athletes uniquely susceptible. Yet despite this well-researched connection, many athletes don't understand their risk. This is partly because athletes are treated as the monolith of good health. But as we've seen, the very activities that earned them this title can put them at fatal risk.

How can we protect our athletes?

Pros and Cons of Emergency Response Plans & Preventative Screenings.

Now that we understand SCA and who it affects, the natural question is: what can be done? The most common approach focuses on stopping SCA as it occurs. When someone experiences cardiac arrest, there's a window of time where they can be resuscitated through cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) or, more critically, through an automated external defibrillator (AED). These methods work by helping the heart regain its normal beating pattern. With this in mind, many institutions, including school campuses and sports teams, develop cardiac emergency response plans (CERPs).

These CERPs outline where the nearest AED is located, provide training to personnel on how to recognize SCA, and when to contact emergency medical services. This is important as every minute without intervention decreases a sudden cardiac arrest victim's chance of survival by approximately 10%.5 Having individuals educated on what to do and resources available, can make the difference between life and death. In theory, this is excellent. In practice, I have reservations. This is not due to the concept itself, but with what's required for a CERP to actually be effective and more accurately what institutions implementing them often overlook:

- Training must be administered to all individuals working at an academic or sports institution, and they must occur consistently to account for staff turnover.

- AEDs must be well-labeled and frequently checked to ensure they're in functioning condition.

- Cardiac emergency response drills must be performed, allowing individuals to practice the skills demonstrated in training.

The reality is that most schools aren't in a position to meet these requirements. With no federal regulations and limited large-scale funding support, many institutions are forced to adopt haphazardly executed emergency action plans.6 A CERP that isn't treated seriously and isn't clearly communicated to all staff is functionally the same as not having one at all. For CERPs to truly address SCA, they need to be treated as mandatory training (similar to fire drills) and implemented universally wherever SCA is most common: schools, sports centers, and gymnasiums.

The other approach to stopping SCA in athletes is preventative electrocardiogram heart screenings. This is a proactive strategy where instead of waiting for cardiac arrest to occur, screenings identify underlying heart abnormalities before they turn fatal.

An electrocardiogram, or EKG, is a test that allows cardiologists to identify cardiac abnormalities by examining the electrical signals that trigger the heart to beat. Variations in these patterns can indicate a variety of conditions, and identifying them early allows for interventions that can prevent SCA.

This seems like the obvious solution: screen all athletes with an EKG prior to play. However, the use of EKGs hasn’t always been viewed favorably. In fact, the nature of preventative screenings and their implementation has been a contentious issue for decades.

Historically, major health organizations—including the American Heart Association—have raised concerns about high false-positive rates leading to unnecessary downstream testing and anxiety, cost considerations for widespread implementation, and inequitable access to services. False positive rates here meaning instances where an EKG indicates there may be an underlying abnormality, but in reality there isn't one.

These criticisms weren't unfounded. With false positive rates in some studies at the time of AHA's statement reporting numbers as high as 11 to 17%, it's understandable why both the scientific and legislative communities pushed back. 7,8 A false reading can have significant emotional impacts on athletes and may result in them being benched during critical moments in their careers, it is a matter that cannot be trivialized.

When discussing the implementation of preventative screenings, these concerns must be fully acknowledged. But these historical criticisms, while valid at the time, have been substantially mitigated by advances in EKG interpretation and athlete-specific screening protocols

Today, we have a much better understanding of the athletic heart thanks to the diligent work of sports cardiologists around the world. When many of these criticisms were being voiced in the early 2010s, the criteria used to interpret EKGs had real issues with sensitivity and produced false positive rates that warranted hesitation. Today, with the International Recommendations for Electrocardiographic Interpretation in Athletes, these screenings are significantly more accurate.

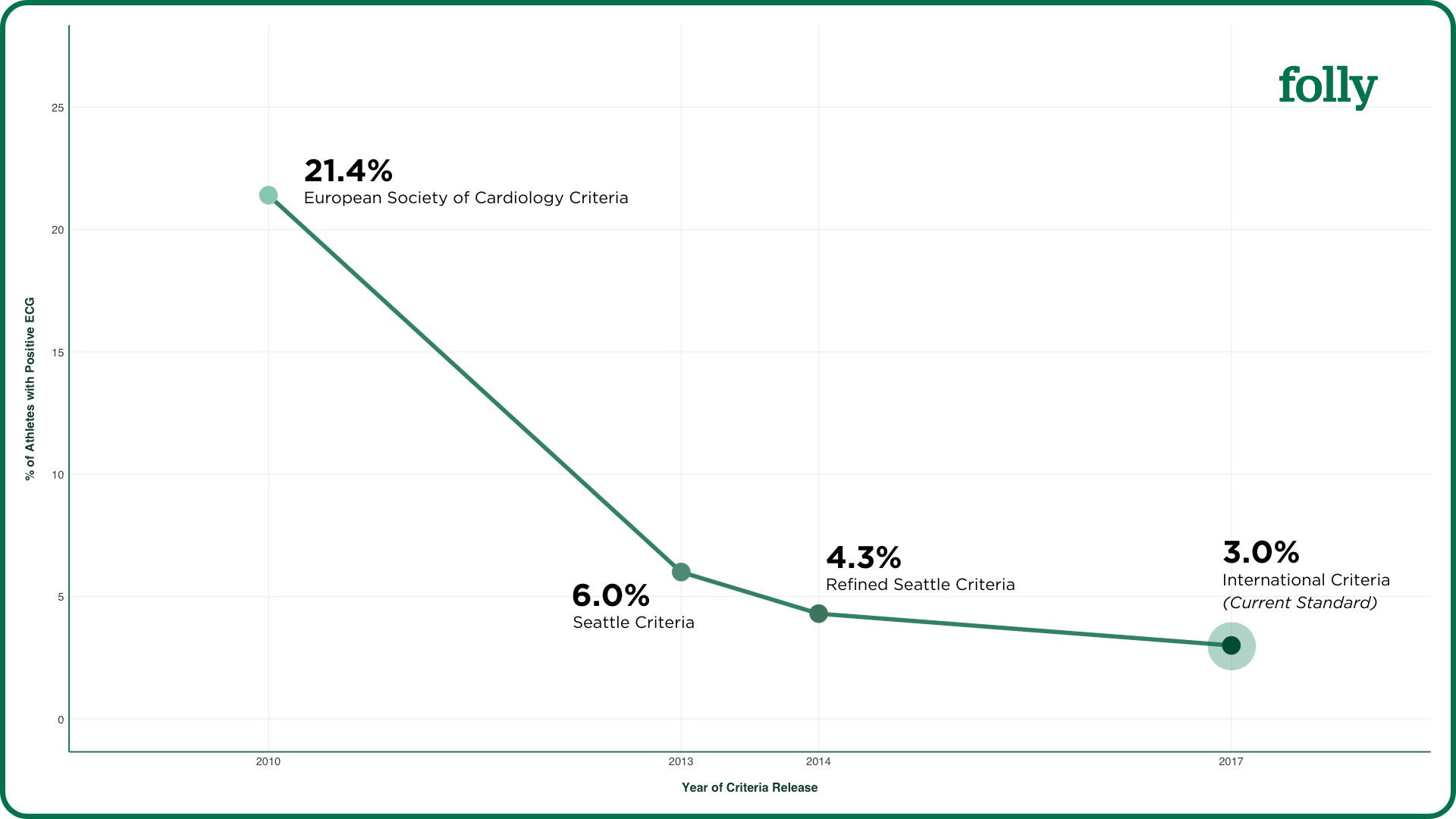

The figure above demonstrates this. It presents data from a retrospective study comparing different EKG interpretation criteria for athletes over time. The authors applied various criteria to the same dataset to determine the percentage of cases that would be flagged as positive and require follow-up. The trend shows substantial improvement in specificity with each successive iteration, with the latest criteria demonstrating over a 17% reduction in cases warranting follow-up care when compared to what was used a decade ago.

This stems largely from recognizing that earlier criteria inappropriately applied the same standards to both athletes and non-athletes. Today, we now understand that certain electrical variations which are life-threatening in the general population are actually normal physiological adaptations in trained athletes.

By accounting for these athlete-specific patterns, the most recent criteria have dramatically reduced unnecessary follow-up testing. This addresses the aforementioned concerns about healthcare system burden, as under modern criteria fewer patients need additional workup. The screening EKG itself remains resource-efficient as it's low-cost and quick to perform (averaging around 5 minutes).

Furthermore, concerns about the financial impact of false positives have been overstated. While some individuals cite secondary testing costs exceeding $10,000, the average cost of screening an athlete after a false positive is approximately $250, typically covering one physician visit and a limited echocardiogram.9

Given this context, for an EKG preventative screening program to be successful, it must meet three criteria: screenings must be interpreted by those familiar with the International Criteria, they must be offered equitably to all athletes regardless of income status, and follow-up care must be ensured if an initial reading suggests an abnormality. It is no longer a matter of if we should do an EKG preventative screening for athletes, but rather how can we ensure they are done properly.

What is next?

Steps to successful prevention, legislation, and what can be done today.

To this point, the article has covered the unique danger SCA poses to athletes and how perspectives on preventative measures have evolved, so it's time to focus on what can be done to ensure no other lives are unnecessarily lost.

On the matter of CERPs, these programs cannot be treated as an afterthought. They need proper funding, staff oversight, and regular practice to ensure safety in spaces like schools where at-risk athletes commonly train and compete. An example of legislation that should serve as a national model is California's Heather Freligh Act.10 It mandates that local educational agencies and county offices of education have procedures in place to respond to individuals experiencing SCA or similar life-threatening medical emergencies. This includes CERPs with CPR training and AED placement based on nationally recognized guidelines.

For preventative screenings, EKGs should be mandatory as part of pre-participation health visits for student athletes. Additionally, they should follow the evolving guidelines set forth by cardiac health organizations and address the accessibility of follow-up care by supplementing screenings with information about equitable clinics. The only state with this mandate is Florida, which passed the Second Chance Act just a few months ago in June 2025. It requires high school student athletes to complete an EKG before athletic competition or tryouts.11

The reality is we're far from addressing this problem at scale. With the scientific community only now reaching consensus on the benefit of EKG screenings for athletes, it will take time for this information to translate into nationwide public policy. In fact, the motivation for this piece was to make in-depth information on this matter more accessible.

I urge you to contact your local representatives and advocate for comprehensive federal mandates for CERPs and preventative EKG screenings. That said, the legislative process is slow and there are many nonprofits that operate in this space that you can support today: The Saving Hearts Foundation, Kyle J. Taylor Foundation, Eric Padres Save a Life Foundation, and Justin Carr Foundation to name a few.

Although the Heather Freligh Act and the Second Chance Act address different aspects of SCA prevention, they share one thing in common: both were spurred by tragedy. Do not let federal change be dictated by loss. The next Act shouldn't have to be named after a young athlete who was afflicted or lost their life, it should be there to prevent it.

References

Sources cited in this article